For my final project I took advantage of free access to Retro City Studios in Germantown (my friend is the owner). I was lucky that some of my former bandmates from Boston were down over Thanksgiving weekend and were happy to do a session while I read some of my favorite Whitman poems. I’m always struck by the music cadence in Whitman’s verse. I think Whitman is best experienced aurally. The background music is original–a collaboration with myself on piano, Adam Garland (guitar), Dave Barbaree (pedal steel), Sven Larson (bass), Steve Turcott (drums), and Brian “Lips” McGrath on trumpet. Hopefully it’s as enjoyable to listen to as it was to record!

Pardon the poor audio quality…

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear,Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong,

The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam,

The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work,

The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deckhand

singing on the steamboat deck,

The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands,

The wood-cutter's song, the ploughboy's on his way in the morning, or

at noon intermission or at sundown,

The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of

the girl sewing or washing,

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else,

The day what belongs to the day—at night the party of young fellows,

robust, friendly,

Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.

SADAKICHI HARTMANN

While doing a search project about Whitman’s racism during his Camden years, I came across an interesting story about a Whitman disciple named Sadakichi Hartmann. Surprisingly, Reynolds does not mention Hartmann in his book.

Whitman’s admiration for Asian civilizations is apparent in his work. In “Passage to India,” he suggests that the complete of the transcontinental railroad as the completion of Columbus’ voyage, and America as a connection between the great civilizations of Europe and Asia. Whitman had a circular view of civilization–Asia as the beginning of civilization, Europe as the absolute end. In “Passage to India,” he even advocates interracial marriage.

Passage to India!

Lo, soul, seest though not God’s purpose from the first?

The earth to be spann’d, connected by network,

The races, neighbors, to marry and be given in marriage,

The oceans to be cross’d, the distant brought near,

the lands to be welded together (Whitman, 532)

Whitman was horrified by the Chinese Exclusion Act passed by Congress in 1882. Whitman threatened to denounce his citizenship in protest saying, “In that narrowest sense, I am not an American—count me out” (Li, 181). He made his view on immigration clear telling Traubel,

“Restrict nothing—keep everything open: to Italy, to China, to anybody. I love America, I believe in America, because her belly can hold and digest all—anarchist, socialist, peacemakers, fighters, disturbers or degenerates of whatever sort—hold and digest all. If I felt that America could not do this I would be indifferent as between our institutions and any others. America is not all in all—the sum total: she is only to contribute her contribution to the big scheme” (Traubel 1:113).

Whitman’s contact with Asian immigrants was rather limited since Camden had only two Chinese-Americans in 1880 and fifty-four in 1890. By 1895, the city directory listed 29 Chinese-run laundries. As their numbers grew, so did anti-Chinese hatred. In the late 1890s, white locals stoned, burned, and dynamited Chinese laundries. Chinese were frequently harassed, beaten, and on a few occasions, murdered (Dorwart, 91).

Whitman’s only known contact with an Asian American in Camden was with Sadakichi Hartmann. He was born in Japan in 1867 to a German father and Japanese mother and raised mostly in Germany. When his father disinherited him for refusing to attend military school, Hartmann immigrated to California. There, he was harassed on suspicion of being a Japanese agent. He moved to Philadelphia to live with an uncle and studied briefly at the Spring Garden Institute. A “dusty bookseller” encouraged Hartmann to visit the poet in Camden telling him, “He is living across the river in Camden and likes to see all sorts of people.” Hartmann visited the poet frequently and became a Whitman disciple, founding a Whitman club. Their relationship soured when Whitman told Hartmann, “There are so many traits, characteristics, Americanisms which you would never get at . . . After all, one can’t grow roses on a peach tree” (Hartmann, 8). Whitman was furious when Hartmann published some of Whitman’s catty remarks about contemporary writers in the New York Herald (Li, 184). The annoyed Whitman questioned Hartmann integrity to Traubel.

“In is in him something basic—something that relates to origins . . . He is a biggish young fellow – has a Tartic face. He is the offspring of a match between a German—the father—and Japanese woman: has the Tartic makeup. And the Asian craftiness, too—all of it!” (Traubel 5:38).

Just before Whitman’s death, Hartmann and his wife visited Whitman and the two made amends. When he learned of Whitman’s death, Hartmann was in New York and unable to afford the train fare to attend Whitman’s funeral. He went to Central Park and “held a silent communion with the soul atoms of the Good Grey Poet, of which a few seem to have wafted to me on the mild March winds” (Hartmann, 50).

Like many of Whitman’s disciples, he wrote a short book detailing his interactions with Whitman. In 1894, he wrote Conversations with Walt Whitman. Hartmann wrote became an early proponent of literary Modernism in the twentieth century. He wrote several volumes of poetry in the early and was one of the first to write English language haikus. He died in 1944.

Works Cited

Dorwart, Jeffrey M. Camden County: the making of a metropolitan community, 1626-2000. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Hartmann, Sadakichi. Conversations with Walt Whitman. New York: Gordon Press, 1972.

Li, Xilao. “Walt Whitman and Asian American Writers.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 10.4 (1993): 179-194. Print.

WILLIAM DOUGLAS O’CONNOR

Walt Whitman described William Douglas O’Connor as his “dear, dear friend, and stanch (probably stanchest) literary believer and champion. . .” (Loving, 1)

O’Connor was born in Boston in 1833. He was a firebrand abolitionist and passionate supporter of liberal causes. At the age of 20, he became the associate editor of The Commonwealth, a daily paper of the anti-slavery Free-Soil movement. He was an editor of the original Saturday Evening Post in Philadelphia from 1854-1860.

He had literary ambitions of his own, writing two unremarkable novels “Harrington” and “The Ghost” in the 1860s. Seeking financial security, he moved to Washington and took on several federal government jobs in the 1860s and 1870s, including a stint as the librarian of the Treasury Department.

Whitman and O’Connor became friends in 1860 when the two were working together at the firm of Thayer and Eldridge in Boston. They met again in Washington during the Civil War, when Whitman rushed down from Brooklyn to look for his brother (who was wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg). Whitman decided to stay in Washington to help the wounded and lived with O’Connor and his family for his first five months in the capital.

O’Connor used his connections to get Whitman a clerkship at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, an undemanding position that gave him plenty of time to write. Whitman was soon fired when the puritanical Secretary of the Interior James Harlan read a copy of Leaves of Grass he found on Whitman’s desk (Reynolds, 455).

Outraged by his friend’s treatment, Douglas wrote The Good Gray Poet in 1866. The self-published 46-page pamphlet passionately defended Whitman’s controversial poetry, argued for literary freedom, and lambasted Harlan for his dismissal of Whitman (Loving, 1). His admiration for the poet is difficult to overstate.

Who, knowing him, does not regard him as a man of the highest spiritual culture? I have never know one of greater and deeper religious feeling. To call one like him good, seems an impertinence. In our sweet country phrase, he is one of the God’s men. And as I write these hurried and broken memoranda—as his strength and sweetness of nature, his moral health, his richness, his courage, his deep and varied knowledge of life and men, his calm wisdom, his singular and beautiful boy-innocence, his personal majesty, his rough scorn of mean actions, his magnetic and exterminating anger on due occasions—all that I have seen and heard of him, the testimony of associates, the anecdotes of friends, the remembrance of hours with him that should be immortal, the traits, lineaments, incidents of his life and being—as they come crowding into memory—his seems to me a character which only the heroic pen of Plutarch could record, and which Socrates himself might emulate of envy (Loving, 167).

Two years later, O’Connor would take his admiration a step further when published “The Carpenter,” a short story in which he compared Whitman to Christ (Reynolds, 463). O’Connor’s wife, Nelly shared in her husband’s devotion to the poet–she even wrote Whitman a letter professing her love for him in 1870.

In 1872, Whitman and O’Connor had a falling out that lasted ten years. Some scholars speculate the two men were having a homosexual quarrel, though there is no evidence to prove they were lovers. Reynolds proposes that the reason for the separation was an intense fight over black voting rights. O’Connor believed passionately in civil rights for freed slaves, Whitman was opposed (Reynolds, 493).

During his quarrel with Whitman, O’Connor also separated from his wife. He continued to defend Whitman’s works. O’Connor reconciled with both his wife and Whitman before his death in 1888, three weeks before Whitman’s seventieth birthday (Reynolds, 543).

Works Cited

Loving, Jerome. Walt Whitman’s Champion. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1978. Print.

Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage

Books, 1996. Print.

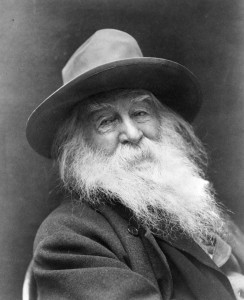

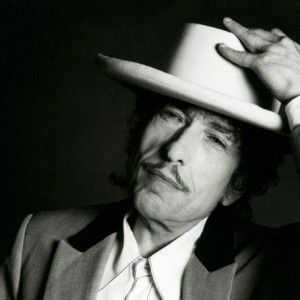

WHITMAN AND DYLAN

While reading “A Backward Glance o’er Travel’d Roads,” I couldn’t help but think of the parallels between the lives of two revolutionary American writers—Walt Whitman and Bob Dylan. Though the poems of Whitman and the lyrics of Bob Dylan have very different formal qualities, both artists have interesting biographical parallels. Have any two artists absorbed their country and time more completely? Both are instantly recognizable as American cultural icons.

Both did their best work in the ‘60s.

Whitman was at the height of his poetic power in the 1860s. The 1860 and 1867 editions of Leaves of Grass included his boldest work, including his magnum opus, the revised “Song of Myself” along with the controversial “Children of Adam”, “Calamus”, and the Civil War series “Drum Taps.” There is no doubt that Whitman wrote his most enduring work during the 1860s.

Dylan did his most revolutionary work in the 1960s. Dylan’s sixties albums are unrivaled by anything in own catalog, with the arguable exception of in 1974’s “Blood on the Tracks.” He broke through with his acoustic protest albums in the early 60s. In the 1965, he alienated his fans by adding electric guitars and a backing rock band. His mid-sixties trilogy “Bringing it All Back Home”, “Highway 61 Revisited”, and “Blonde on Blonde”, are among the most studied and influential albums in rock and popular music history. His hit “Like A Rolling Stone” redefined the boundaries of length and lyrics in a pop song.

Both were celebrated in England.

Whitman and Dylan were not readily absorbed by the mainstream American public. Both had influential disciples in England who promoted their work. British poet William Michael Rossetti wrote a favorable article about Leaves of Grass in 1867 in the London Chronicle, leading the an eventual publication of a expurgated version of the book in Britain.

Dylan packed theaters across Britain during his 1964 tour. D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary Don’t Look Back shows how revered he was in Britain. His British disciples included the Beatles, whom Dylan famously introduced to marijuana.

Both grew up in rural areas and moved to Manhattan to become artists

Dylan grew up in tiny Hibbing, Minnesota. After a brief stint at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, he moved to Greenwich Village in 1962 to become part of New York’s thriving folk scene.

Whitman was born rural West Hills, Long Island, and grew up in Brooklyn, which, during Whitman’s youth, was still largely rural. Whitman crossed Brooklyn ferry for good in the 1840s for the big time in Manhattan.

Both lost their artistic power in the ‘80s.

Whitman’s work from the 1880s is among his most forgettable. His “Sands at Seventy” annexes to Leaves of Grass have nothing new to say, as Whitman himself admits. With a few exceptions, his late poems are sleepers—based on tired metaphors and delivered in stilted language. Gone is the rebel spirit of the 1850 and 1860s. Whitman, unlike Dylan, had old age to blame.

Dylan’s work in the 1980s was not the result of old-age weakness, but a lapse in taste. He dabbled in a preachy, judgmental form of Christian rock in “Slow Train Coming” and “Saved.” Perhaps the worst Dylan songs ever came on his 1983 album “Infidels”—“Jokerman” and “Neighborhood Bully” are both strong contenders for worst Dylan song ever. After achieving great success, both Dylan and Whitman were “phoning it in.” Experiments later in the decade with sequenced drums were equally disastrous.

Both absorbed their country and times

Though he rejected the label, Dylan was often called the “voice of his generation.” His earlier topical songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” will forever tie him to the Civil Rights movement and the 1960s, a lingering legacy of the Civil War’s unfinished business. The Civil War was the defining event of Whitman’s life. His work before and during the war remains his most powerful.

Both lied to the press to help their careers

Before he was famous, Dylan frequently lied to reporters about his background. Dylan told an interviewer in 1962 that he worked for six years as a clean-up boy at the carnival. Actually, Dylan grew up in an upper middle-class family and had his own car in high school. Whitman was a master at manipulating the press. On several occasions he forged letters to the press in order to create his own myth.

Both were far more influential than their commercial success would indicate

Dylan, despite being the most influential songwriter of his generation, has never had a number one hit song. “Like a Rolling Stone” was his highest-charting song at number two. Rolling Stone named it the number one song of all time in 2005. The Scorpions have sold more albums. Covers of Dylan’s song are often more popular than the originals. Admittedly, Dylan isn’t struggling financially. His record sales, while impressive, are not among the top 50 performers of all time. Dylan had tremendous influence over the The Beatles (post 1965), Nick Cave, Bruce Springsteen, Joe Cocker, Tom Petty, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Paul Simon, and the Velvet Underground among countless others.

Whitman’s Leaves of Grass did not sell enough copies to make Whitman a wealthy man. Whitman felt neglected by the public writing in “A Backward Glance O’er Travel’d Roads” that ““from a worldly and business point of view ‘Leave of Grass’ has been worse than a failure—that public criticism on the book and myself as author of it yet shows the mark’d anger and contempt more than anything else.” However, Whitman was not as neglected wanted the public to think. Historical figures like Andrew Carnegie, Ezra Pound, Edith Wharton, Bram Stoker, Oscar Wilde, Adrienne Rich, Alan Ginsburg have paid homage to Whitman. “If you are American, then Walt Whitman is your imaginative father and mother, even if, like myself, you have never composed a line of verse. You can nominate a fair number of literary works as candidates for the secular Scripture of the United States. They might include Melville’s Moby-Dick, Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Emerson’s two series of Essays and The Conduct of Life. None of those, not even Emerson’s, are as central as the first edition of Leaves of Grass,” Harold Bloom wrote about Whitman.

Works Cited

Reynold, David. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage, 1998.

Bloom Harold. Introduction to Leaves of Grass. New York: Penguin Books, 2005.

Sounes, Howard. Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan. New York: Grove Press, 2001.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well, then, I contradict myself

(I am large, I contain multitudes)

–Walt Whitman

Nowhere did Whitman contradict himself more than in his racial attitudes. Whitman is celebrated as an egalitarian poet who transcended the racism of his time. Outside his poetry, he frequently made racist statements, both as a young journalist and old man. Whitman’s record on race seems to be a perplexing mix of prejudice and admiration. Of particular interest is an article I found by Xiao Li published in Walt Whitman Quarterly.

Li looks at Whitman’s relationship with Asian-Americans. Whitman was horrified by anti-Chinese immigration laws passed in the 1880s, even threatening to denounce his citizenship. Whitman supported unlimited, unrestricted immigration from all countries. Li recounts the story of Sadakichi Hartmann, a half-German, half Japanese immigrant who was born in Japan. While a student in Philadelphia, Hartmann sought out the aging poet in Camden. Hartmann became a Whitman disciple, but their relationship soured when Whitman told Hartmann, “There are so many traits, characteristics, Americanisms which you would never get at . . . After all, one can’t grow roses on a peach tree.” Hartmann’s publication of these remarks angered the poet, who told Traubel that Hartmann possessed the “Asian craftiness.” The two men made peace shortly before Whitman’s death. The Hartmann story might be the best anecdote to outline Whitman’s racial contradictions.

Li, Xilao. “Walt Whitman and Asian American Writers.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 10.4 (1993): 179-194. Print.

Whitman,%20Camden,%20and%20Race[1]click here for my bibliographic essay about Whitman’s racial attitudes

On May 31, 1889, Walt Whitman’s seventieth birthday, 2,209 people were killed when the South Fork Dam failed, sending a wall rushing water and debris cascading into the riverside town of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. It was the largest civilian loss of life in American history up to that time (McCullough, 4). It was also one of the first major disaster relief efforts led by the American Red Cross, under the direction of Clara Barton.

The dam, located 14 miles upstream from Johnstown, held back the artificial Lake Conemaugh, a canal basin that the state never completed due to emergence of the railroad. The lake was sold to private interests and became part of the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club, playground for wealthy Pittsburgh steel executives. The owners had made questionable modifications to the dam, lowering it in order to build a road on top of it. These modifications, along with poor maintenance and record rainfall were blamed for the dam’s failure.

On May 30, 1889, a storm swept over western Pennsylvania from the Midwest dumping six to ten inches of rain over western Pennsylvania. The following day, as Lake Conemaugh swelled, an impromptu team of men tried to clear debris from the dam spillway. At 3:10, the dam burst and the lake spilled into the narrow Little Conemaugh River, picking up houses, farm animals, people, barns, bridges, barbed wire, and train cars as it moved downstream. By the time the water and debris reached Johnstown, eyewitnesses reported it was 40 feet high and a half-mile wide (Loving, 116). At least 80 people died in the fires the followed as the debris that had piled up behind a rail bridge began to burn. Four square miles of Johnstown were completely destroyed. 1600 homes were lost. 2209 people, including 396 children and 99 entire families perished.

By the evening, the storm had reached Camden, where Walt Whitman and his supporters were celebrating the poet’s seventieth birthday party at Morgan’s Hall. Whitman was deeply saddened by the disaster. He found it ironic that the tragedy occurred during the height of his birthday celebration (Reynolds, 573).

Horace Traubel recorded Whitman’s remarks six days after flood.

8 P.M. Went down to W.’s with Harned, finding W. sitting in parlor at the window. Had but a little time before returned from his outing. Talked directly of the Johnstown affair. “It seems to hang over us all like a cloud,” he said—”a dark, dark, dark cloud.” And then he asked: “Do you think this Cambria matter interferes at all with the passage of the mails? We all live in Cambria County now (Traubel, 264).

Whitman wrote “A Voice from Death” about the flood victims. The poem was published in the New York World on June 7, 1889, only a week after the flood. Whitman was paid $25.

With sudden, indescribable blow–towns drown’d–humanity by

thousands slain,

The vaunted work of thrift, goods, dwellings, forge, street, iron bridge,

Dash’d pell-mell by the blow–yet usher’d life continuing on,

(Amid the rest, amid the rushing, whirling, wild debris,

A suffering woman saved–a baby safely born!)

Although I come and unannounc’d, in horror and in pang,

In pouring flood and fire, and wholesale elemental crash, (this

voice so solemn, strange,)

I too a minister of Deity.

Yea, Death, we bow our faces, veil our eyes to thee,

We mourn the old, the young untimely drawn to thee,

The fair, the strong, the good, the capable,

The household wreck’d, the husband and the wife, the engulfed forger

in his forge,

The corpses in the whelming waters and the mud,

The gather’d thousands to their funeral mounds, and thousands never

found or gather’d.

Then after burying, mourning the dead,

(Faithful to them found or unfound, forgetting not, bearing the

past, here new musing,)

A day–a passing moment or an hour–America itself bends low,

Silent, resign’d, submissive.

War, death, cataclysm like this, America,

Take deep to thy proud prosperous heart.

E’en as I chant, lo! out of death, and out of ooze and slime,

The blossoms rapidly blooming, sympathy, help, love,

From West and East, from South and North and over sea,

Its hot-spurr’d hearts and hands humanity to human aid moves on;

And from within a thought and lesson yet.

Thou ever-darting Globe! through Space and Air!

Thou waters that encompass us!

Thou that in all the life and death of us, in action or in sleep!

Thou laws invisible that permeate them and all,

Thou that in all, and over all, and through and under all, incessant!

Thou! thou! the vital, universal, giant force resistless, sleepless, calm,

Holding Humanity as in thy open hand, as some ephemeral toy,

How ill to e’er forget thee!

For I too have forgotten,

(Wrapt in these little potencies of progress, politics, culture,

wealth, inventions, civilization,)

Have lost my recognition of your silent ever-swaying power, ye

mighty, elemental throes,

In which and upon which we float, and every one of us is buoy’d.

Work Cited

Loving, Jerome “The Political Roots of Leaves of Grass.” A Historical Guide to Walt Whitman. Ed. David S. Reynolds.New York, NY: Oxford UP (2000): 116-117. Google Books. Web. 20 Oct. 2009.

McCullough, David G. The Johnstown Flood. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1967. 4-81. Google Books. Web. 20 Oct. 2009.

Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. Print.

Traubel, Horace. With Walt Whitman in Camden Volume 5. Ed. Gertrude Traubel. Carbondale: U of Southern Illinois P, 1964. Google Books. Web. 21 Oct. 2009.

Whitman, Walt. “A Voice from Death.” Whitman Poetry & Prose. Library of America College Editions, 1996. Print.

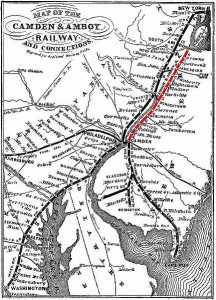

Camden’s role as a rail hub led to its rapid industrial growth in the nineteenth century. In the 1880s, the city had six railroads. Among the most important were the Camden and Amboy, and the Camden and Atlantic.

The Camden and Amboy Railroad was the first railroad in New Jersey one first in the United States. It was completed in 1834, connecting Camden to South Amboy on the Raritan River, where passengers could continue via ferry to New York City. Though it was called the Camden and Amboy Railroad, its real purpose was to monopolize travel through New Jersey between Philadelphia and New York City. It was the first railroad to use the all-iron flanged “T” rail, which would become standard on all US railroads (Lorett, 8).

The State of New Jersey granted the Delaware & Raritan Canal Company & Camden & Amboy Railroad and Transportation Company a limited-time monopoly in exchange for 1000 shares of the company.

Ownership of the Camden and Amboy Railroad changed several times over the nineteenth century through a complicated series of mergers, acquisitions, and leases. The Philadelphia and Trenton Railroad opened in 1836, offering a more direct route to New York City. However, the P&T terminal was inconveniently located in Kensington, far from Center City. Most passengers preferred to take the Camden and Amboy because its waterfront terminal was easily reached by ferry from Philadelphia.

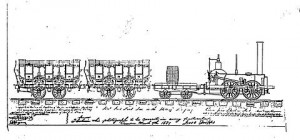

Perhaps more famous than the railroad itself was John Bull, the original steam locomotive that served the railroad until 1866. The locomotive was built in Newcastle, England (no American company built locomotives at that time) dismantled and shipped without instructions on how to put it together. Camden and Amboy engineer Isaac Dripps reassembled it according to his intuition. The engine was originally called the Stevens, in honor of the railroad’s founder Robert L. Stevens. Over time, the crew began calling it the “Old John Bull” in a reference tothe cartoon caricature of Great Britain, similar to America’s Uncle Sam. In 1981, the John Bull was started up again, making it the world’s oldest running locomotive. It is currently in the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History.

Just a few blocks south was another important railroad, the Camden and Atlantic, which connected Camden to Atlantic City in trip that took just over an hour. Completed in 1854, the railroad was instrumental in transforming a thinly inhabited island to a thriving resort town. In fact, the Camden and Atlantic’s board of directors founded and planned the city. Atlantic City’s grid pattern intentionally copied Philadelphia’s, so that tourists from Philadelphia wouldn’t get lost in the resort city. The famous Boardwalk was the brainchild of Camden and Atlantic conductor Alexander Boardman. Atlantic City was a major summer escape for sweltering middle class city dwellers during the nineteenth century. Whitman frequently used to railroad to visit the Atlantic shore.

WHITMAN AND RAILROADS

Railroads were a theme in Whitman’s writing before he moved to Camden in 1874. For the poet, railroads were a powerful, unifying symbol of the modern age, the “pulse of the continent” (Nye, 172). He celebrates railroads in his 1870 poem “Passage to India.”

The earth to be spann’d connected by network

The races, neighbors, to marry and be given in marriage

The oceans to be cross’d, the distant brought near,

The lands to be welded together.

A new worship I sing,

You captains, voyagers, explorers, yours,

You engineers, you architects, machinists, yours

But in God’s name, and for thy sake O soul.

Historian David E. Nye wrote: “ . . . for Whitman the train was a part of a larger ‘passage to India’ that would link the Atlantic and Pacific and place the United States at the center of world commerce. He saw this “marriage of continents, climates and oceans” as more than the completion of Columbus’ voyages, for it intimated transcendent journey to the stars. . . The force of the locomotive became symbolic of the power to remake the land and to found new communities.” (Nye, 172).

Whitman mentions the Camden and Amboy Railroad in a letter from 1874, when he was living with his brother on nearby Stevens Street.

“The trains of the Camden & Amboy are going by on the track about 50 or 60 rods from here, puffing & blowing – often train after train, following each other – following each other – & locomotives singly, whisking & squealing, up the track & then down again – I often sit and watch them long … ”

It is likely that the trains from the Camden and Amboy Railroad inspired his 1876 poem “To a Locomotive in Winter”. The legendary John Bull locomotive was retired in 1866, before Whitman moved to Camden, so it is doubtful that he is referring to it here.

Thee for my recitative,

Thee in the driving storm even as now, the snow, the winter-day declining,

Thee in thy panoply, thy measur’d dual throbbing and thy beat convulsive,

Thy black cylindric body, golden brass and silvery steel,

Thy ponderous side-bars, parallel and connecting rods, gyrating,

shuttling at thy sides,

Thy metrical, now swelling pant and roar, now tapering in the distance,

Thy great protruding head-light fix’d in front,

Thy long, pale, floating vapor-pennants, tinged with delicate purple,

The dense and murky clouds out-belching from thy smoke-stack,

Thy knitted frame, thy springs and valves, the tremulous twinkle of

thy wheels,

Thy train of cars behind, obedient, merrily following,

Through gale or calm, now swift, now slack, yet steadily careering;

Type of the modern–emblem of motion and power–pulse of the continent,

For once come serve the Muse and merge in verse, even as here I see thee,

With storm and buffeting gusts of wind and falling snow,

By day thy warning ringing bell to sound its notes,

By night thy silent signal lamps to swing.

Fierce-throated beauty!

Roll through my chant with all thy lawless music, thy swinging lamps

at night,

Thy madly-whistled laughter, echoing, rumbling like an earthquake,

rousing all,

Law of thyself complete, thine own track firmly holding,

(No sweetness debonair of tearful harp or glib piano thine,)

Thy trills of shrieks by rocks and hills return’d,

Launch’d o’er the prairies wide, across the lakes,

To the free skies unpent and glad and strong.

The Camden and Amboy tracks ran just feet from the house at 328 Mickle Street where Whitman lived from 1884 until his death. The house was a short walk from the railroad’s terminus on the Camden waterfront.

REMNANTS TODAY

The legacy of these pioneering railroads lives on today. Both the Camden and Amboy and the Camden and Atlantic paths are still in use. The Camden and Amboy is now New Jersey Transit’s River Line, which opened in 1999. The River Line follows the exact Camden and Amboy path from just outside Camden to Trenton. Much of the route looks the same as it did in Whitman’s time, especially the scenic section between Bordentown and Trenton, where the line passes through Hamilton marsh. The Camden and Atlantic Railroad is now New Jersey Transit’s Atlantic City Line, which shares portions of its right of way with the PATCO High Speed Line and Amtrak.

Works Cited

Lorett, Treese. Railroads of New Jersey: Fragments of the Past in the Garden State

Landscape. Mechanicsburg, Penn: Stackpole Books, 2006. Google Books.

Web. 15 Oct. 2009.

Nye, David E. America as Second Creation: Technology and Narratives of New

Beginnings. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2003. Google Books. Web. 15 Oct.

2009

Whitman, Walt. Whitman Poetry & Prose. Library of America College Editions 1996.

Print.

As a Civil War nerd, I found Whitman’s war memoranda very informative and enjoyable. His account of soldiers returning after the Battle of Bull Run shows a side of the war I didn’t know–that there was widespread doubt among Union soldiers about their ability to win.

The contrast between Whitman’s poetry and prose is striking. Is seems Whitman was bipolar. Gone is the sensuous, grandiose poetic language; Whitman’s prose is straightforward and conventional. Reading Whitman stripped of his literary devices is like seeing an interview of an actor out of character. In his prose, it’s about the story itself, not how it’s told. The purpose of “Specimen Days” is to relate history, not dazzle the readers. In “Specimen Days” we have a primary source from just behind the front lines of the Civil War, free of retrospect. What we have from Whitman the voice of a marginal character–not an officer, not a solider, not even a real nurse, but a lowly hospital assistant. Whitman’s sensitivity and humanity come through in interactions with sick and dying soldiers. Surprisingly, he deals with death and dying quite matter-of-factly, not something you’d expect from a romantic poet. In this excerpt from “Down at the Front” he sounds more like Hemingway than the man who wrote “Song of Myself.”

Out doors, at the foot of a tree, within ten yards of the front of the house, I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c., a full load for a one-horse cart. Several dead bodies lie near, each cover’d with its brown woolen blanket. In the door-yard, towards the river, are fresh graves, mostly of officers, their names on pieces of barrel-staves or broken boards, stuck in the dirt. (Most of these bodies were subsequently taken up and transported north to their friends.) The large mansion is quite crowded upstairs and down, everything impromptu, no system, all bad enough, but I have no doubt the best that can be done; all the wounds pretty bad, some frightful, the men in their old clothes, unclean and bloody. Some of the wounded are rebel soldiers and officers, prisoners. One, a Mississippian, a captain, hit badly in leg, I talk’d with some time; he ask’d me for papers, which I gave him. (I saw him three months afterward in Washington, with his leg amputated, doing well.) I went through the rooms, downstairs and up. Some of the men were dying. I had nothing to give at that visit, but wrote a few letters to folks home, mothers.

Another revealing passage is his account of Abraham Lincoln on p. 736. We have come to think of Lincoln, and the presidency in general, as something far removed from the daily life of citizens. Who would’ve guessed that an ordinary man like Whitman could follow the daily comings and goings of the president as if he were just a neighbor? Whitman could get close enough to the president to see the “deep-cut lines, the eyes, always to me with a deep latent sadness in the expression. We have got so that we exchange bows and very cordial ones.” Imagine a regular citizen having such casual rapport with a president today. Today, the closest a ordinary person can get to the president is to peek through the gates on Pennsylvania avenue and watch the snipers on the roof of the White House. Or maybe the glimpse of Obama’s waving hand from his motorcade. Times have changed.