For my final project I took advantage of free access to Retro City Studios in Germantown (my friend is the owner). I was lucky that some of my former bandmates from Boston were down over Thanksgiving weekend and were happy to do a session while I read some of my favorite Whitman poems. I’m always struck by the music cadence in Whitman’s verse. I think Whitman is best experienced aurally. The background music is original–a collaboration with myself on piano, Adam Garland (guitar), Dave Barbaree (pedal steel), Sven Larson (bass), Steve Turcott (drums), and Brian “Lips” McGrath on trumpet. Hopefully it’s as enjoyable to listen to as it was to record!

Archive for » December, 2009 «

Pardon the poor audio quality…

I hear America singing, the varied carols I hear,Those of mechanics, each one singing his as it should be blithe and strong,

The carpenter singing his as he measures his plank or beam,

The mason singing his as he makes ready for work, or leaves off work,

The boatman singing what belongs to him in his boat, the deckhand

singing on the steamboat deck,

The shoemaker singing as he sits on his bench, the hatter singing as he stands,

The wood-cutter's song, the ploughboy's on his way in the morning, or

at noon intermission or at sundown,

The delicious singing of the mother, or of the young wife at work, or of

the girl sewing or washing,

Each singing what belongs to him or her and to none else,

The day what belongs to the day—at night the party of young fellows,

robust, friendly,

Singing with open mouths their strong melodious songs.

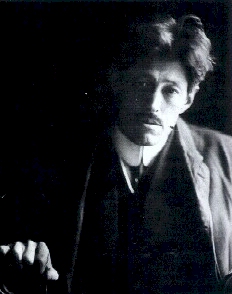

SADAKICHI HARTMANN

While doing a search project about Whitman’s racism during his Camden years, I came across an interesting story about a Whitman disciple named Sadakichi Hartmann. Surprisingly, Reynolds does not mention Hartmann in his book.

Whitman’s admiration for Asian civilizations is apparent in his work. In “Passage to India,” he suggests that the complete of the transcontinental railroad as the completion of Columbus’ voyage, and America as a connection between the great civilizations of Europe and Asia. Whitman had a circular view of civilization–Asia as the beginning of civilization, Europe as the absolute end. In “Passage to India,” he even advocates interracial marriage.

Passage to India!

Lo, soul, seest though not God’s purpose from the first?

The earth to be spann’d, connected by network,

The races, neighbors, to marry and be given in marriage,

The oceans to be cross’d, the distant brought near,

the lands to be welded together (Whitman, 532)

Whitman was horrified by the Chinese Exclusion Act passed by Congress in 1882. Whitman threatened to denounce his citizenship in protest saying, “In that narrowest sense, I am not an American—count me out” (Li, 181). He made his view on immigration clear telling Traubel,

“Restrict nothing—keep everything open: to Italy, to China, to anybody. I love America, I believe in America, because her belly can hold and digest all—anarchist, socialist, peacemakers, fighters, disturbers or degenerates of whatever sort—hold and digest all. If I felt that America could not do this I would be indifferent as between our institutions and any others. America is not all in all—the sum total: she is only to contribute her contribution to the big scheme” (Traubel 1:113).

Whitman’s contact with Asian immigrants was rather limited since Camden had only two Chinese-Americans in 1880 and fifty-four in 1890. By 1895, the city directory listed 29 Chinese-run laundries. As their numbers grew, so did anti-Chinese hatred. In the late 1890s, white locals stoned, burned, and dynamited Chinese laundries. Chinese were frequently harassed, beaten, and on a few occasions, murdered (Dorwart, 91).

Whitman’s only known contact with an Asian American in Camden was with Sadakichi Hartmann. He was born in Japan in 1867 to a German father and Japanese mother and raised mostly in Germany. When his father disinherited him for refusing to attend military school, Hartmann immigrated to California. There, he was harassed on suspicion of being a Japanese agent. He moved to Philadelphia to live with an uncle and studied briefly at the Spring Garden Institute. A “dusty bookseller” encouraged Hartmann to visit the poet in Camden telling him, “He is living across the river in Camden and likes to see all sorts of people.” Hartmann visited the poet frequently and became a Whitman disciple, founding a Whitman club. Their relationship soured when Whitman told Hartmann, “There are so many traits, characteristics, Americanisms which you would never get at . . . After all, one can’t grow roses on a peach tree” (Hartmann, 8). Whitman was furious when Hartmann published some of Whitman’s catty remarks about contemporary writers in the New York Herald (Li, 184). The annoyed Whitman questioned Hartmann integrity to Traubel.

“In is in him something basic—something that relates to origins . . . He is a biggish young fellow – has a Tartic face. He is the offspring of a match between a German—the father—and Japanese woman: has the Tartic makeup. And the Asian craftiness, too—all of it!” (Traubel 5:38).

Just before Whitman’s death, Hartmann and his wife visited Whitman and the two made amends. When he learned of Whitman’s death, Hartmann was in New York and unable to afford the train fare to attend Whitman’s funeral. He went to Central Park and “held a silent communion with the soul atoms of the Good Grey Poet, of which a few seem to have wafted to me on the mild March winds” (Hartmann, 50).

Like many of Whitman’s disciples, he wrote a short book detailing his interactions with Whitman. In 1894, he wrote Conversations with Walt Whitman. Hartmann wrote became an early proponent of literary Modernism in the twentieth century. He wrote several volumes of poetry in the early and was one of the first to write English language haikus. He died in 1944.

Works Cited

Dorwart, Jeffrey M. Camden County: the making of a metropolitan community, 1626-2000. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Hartmann, Sadakichi. Conversations with Walt Whitman. New York: Gordon Press, 1972.

Li, Xilao. “Walt Whitman and Asian American Writers.” Walt Whitman Quarterly Review 10.4 (1993): 179-194. Print.

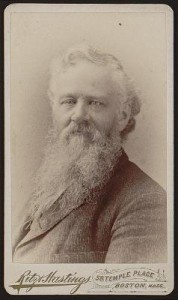

WILLIAM DOUGLAS O’CONNOR

Walt Whitman described William Douglas O’Connor as his “dear, dear friend, and stanch (probably stanchest) literary believer and champion. . .” (Loving, 1)

O’Connor was born in Boston in 1833. He was a firebrand abolitionist and passionate supporter of liberal causes. At the age of 20, he became the associate editor of The Commonwealth, a daily paper of the anti-slavery Free-Soil movement. He was an editor of the original Saturday Evening Post in Philadelphia from 1854-1860.

He had literary ambitions of his own, writing two unremarkable novels “Harrington” and “The Ghost” in the 1860s. Seeking financial security, he moved to Washington and took on several federal government jobs in the 1860s and 1870s, including a stint as the librarian of the Treasury Department.

Whitman and O’Connor became friends in 1860 when the two were working together at the firm of Thayer and Eldridge in Boston. They met again in Washington during the Civil War, when Whitman rushed down from Brooklyn to look for his brother (who was wounded at the Battle of Fredericksburg). Whitman decided to stay in Washington to help the wounded and lived with O’Connor and his family for his first five months in the capital.

O’Connor used his connections to get Whitman a clerkship at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, an undemanding position that gave him plenty of time to write. Whitman was soon fired when the puritanical Secretary of the Interior James Harlan read a copy of Leaves of Grass he found on Whitman’s desk (Reynolds, 455).

Outraged by his friend’s treatment, Douglas wrote The Good Gray Poet in 1866. The self-published 46-page pamphlet passionately defended Whitman’s controversial poetry, argued for literary freedom, and lambasted Harlan for his dismissal of Whitman (Loving, 1). His admiration for the poet is difficult to overstate.

Who, knowing him, does not regard him as a man of the highest spiritual culture? I have never know one of greater and deeper religious feeling. To call one like him good, seems an impertinence. In our sweet country phrase, he is one of the God’s men. And as I write these hurried and broken memoranda—as his strength and sweetness of nature, his moral health, his richness, his courage, his deep and varied knowledge of life and men, his calm wisdom, his singular and beautiful boy-innocence, his personal majesty, his rough scorn of mean actions, his magnetic and exterminating anger on due occasions—all that I have seen and heard of him, the testimony of associates, the anecdotes of friends, the remembrance of hours with him that should be immortal, the traits, lineaments, incidents of his life and being—as they come crowding into memory—his seems to me a character which only the heroic pen of Plutarch could record, and which Socrates himself might emulate of envy (Loving, 167).

Two years later, O’Connor would take his admiration a step further when published “The Carpenter,” a short story in which he compared Whitman to Christ (Reynolds, 463). O’Connor’s wife, Nelly shared in her husband’s devotion to the poet–she even wrote Whitman a letter professing her love for him in 1870.

In 1872, Whitman and O’Connor had a falling out that lasted ten years. Some scholars speculate the two men were having a homosexual quarrel, though there is no evidence to prove they were lovers. Reynolds proposes that the reason for the separation was an intense fight over black voting rights. O’Connor believed passionately in civil rights for freed slaves, Whitman was opposed (Reynolds, 493).

During his quarrel with Whitman, O’Connor also separated from his wife. He continued to defend Whitman’s works. O’Connor reconciled with both his wife and Whitman before his death in 1888, three weeks before Whitman’s seventieth birthday (Reynolds, 543).

Works Cited

Loving, Jerome. Walt Whitman’s Champion. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1978. Print.

Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage

Books, 1996. Print.