WHITMAN AND DYLAN

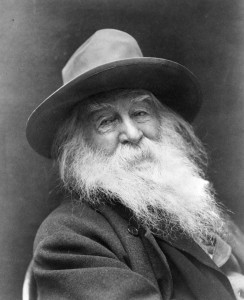

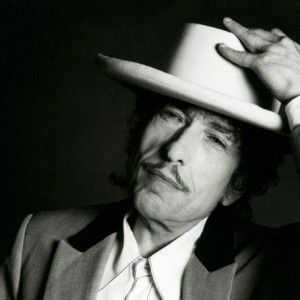

While reading “A Backward Glance o’er Travel’d Roads,” I couldn’t help but think of the parallels between the lives of two revolutionary American writers—Walt Whitman and Bob Dylan. Though the poems of Whitman and the lyrics of Bob Dylan have very different formal qualities, both artists have interesting biographical parallels. Have any two artists absorbed their country and time more completely? Both are instantly recognizable as American cultural icons.

Both did their best work in the ‘60s.

Whitman was at the height of his poetic power in the 1860s. The 1860 and 1867 editions of Leaves of Grass included his boldest work, including his magnum opus, the revised “Song of Myself” along with the controversial “Children of Adam”, “Calamus”, and the Civil War series “Drum Taps.” There is no doubt that Whitman wrote his most enduring work during the 1860s.

Dylan did his most revolutionary work in the 1960s. Dylan’s sixties albums are unrivaled by anything in own catalog, with the arguable exception of in 1974’s “Blood on the Tracks.” He broke through with his acoustic protest albums in the early 60s. In the 1965, he alienated his fans by adding electric guitars and a backing rock band. His mid-sixties trilogy “Bringing it All Back Home”, “Highway 61 Revisited”, and “Blonde on Blonde”, are among the most studied and influential albums in rock and popular music history. His hit “Like A Rolling Stone” redefined the boundaries of length and lyrics in a pop song.

Both were celebrated in England.

Whitman and Dylan were not readily absorbed by the mainstream American public. Both had influential disciples in England who promoted their work. British poet William Michael Rossetti wrote a favorable article about Leaves of Grass in 1867 in the London Chronicle, leading the an eventual publication of a expurgated version of the book in Britain.

Dylan packed theaters across Britain during his 1964 tour. D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary Don’t Look Back shows how revered he was in Britain. His British disciples included the Beatles, whom Dylan famously introduced to marijuana.

Both grew up in rural areas and moved to Manhattan to become artists

Dylan grew up in tiny Hibbing, Minnesota. After a brief stint at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, he moved to Greenwich Village in 1962 to become part of New York’s thriving folk scene.

Whitman was born rural West Hills, Long Island, and grew up in Brooklyn, which, during Whitman’s youth, was still largely rural. Whitman crossed Brooklyn ferry for good in the 1840s for the big time in Manhattan.

Both lost their artistic power in the ‘80s.

Whitman’s work from the 1880s is among his most forgettable. His “Sands at Seventy” annexes to Leaves of Grass have nothing new to say, as Whitman himself admits. With a few exceptions, his late poems are sleepers—based on tired metaphors and delivered in stilted language. Gone is the rebel spirit of the 1850 and 1860s. Whitman, unlike Dylan, had old age to blame.

Dylan’s work in the 1980s was not the result of old-age weakness, but a lapse in taste. He dabbled in a preachy, judgmental form of Christian rock in “Slow Train Coming” and “Saved.” Perhaps the worst Dylan songs ever came on his 1983 album “Infidels”—“Jokerman” and “Neighborhood Bully” are both strong contenders for worst Dylan song ever. After achieving great success, both Dylan and Whitman were “phoning it in.” Experiments later in the decade with sequenced drums were equally disastrous.

Both absorbed their country and times

Though he rejected the label, Dylan was often called the “voice of his generation.” His earlier topical songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind” will forever tie him to the Civil Rights movement and the 1960s, a lingering legacy of the Civil War’s unfinished business. The Civil War was the defining event of Whitman’s life. His work before and during the war remains his most powerful.

Both lied to the press to help their careers

Before he was famous, Dylan frequently lied to reporters about his background. Dylan told an interviewer in 1962 that he worked for six years as a clean-up boy at the carnival. Actually, Dylan grew up in an upper middle-class family and had his own car in high school. Whitman was a master at manipulating the press. On several occasions he forged letters to the press in order to create his own myth.

Both were far more influential than their commercial success would indicate

Dylan, despite being the most influential songwriter of his generation, has never had a number one hit song. “Like a Rolling Stone” was his highest-charting song at number two. Rolling Stone named it the number one song of all time in 2005. The Scorpions have sold more albums. Covers of Dylan’s song are often more popular than the originals. Admittedly, Dylan isn’t struggling financially. His record sales, while impressive, are not among the top 50 performers of all time. Dylan had tremendous influence over the The Beatles (post 1965), Nick Cave, Bruce Springsteen, Joe Cocker, Tom Petty, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Paul Simon, and the Velvet Underground among countless others.

Whitman’s Leaves of Grass did not sell enough copies to make Whitman a wealthy man. Whitman felt neglected by the public writing in “A Backward Glance O’er Travel’d Roads” that ““from a worldly and business point of view ‘Leave of Grass’ has been worse than a failure—that public criticism on the book and myself as author of it yet shows the mark’d anger and contempt more than anything else.” However, Whitman was not as neglected wanted the public to think. Historical figures like Andrew Carnegie, Ezra Pound, Edith Wharton, Bram Stoker, Oscar Wilde, Adrienne Rich, Alan Ginsburg have paid homage to Whitman. “If you are American, then Walt Whitman is your imaginative father and mother, even if, like myself, you have never composed a line of verse. You can nominate a fair number of literary works as candidates for the secular Scripture of the United States. They might include Melville’s Moby-Dick, Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Emerson’s two series of Essays and The Conduct of Life. None of those, not even Emerson’s, are as central as the first edition of Leaves of Grass,” Harold Bloom wrote about Whitman.

Works Cited

Reynold, David. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage, 1998.

Bloom Harold. Introduction to Leaves of Grass. New York: Penguin Books, 2005.

Sounes, Howard. Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan. New York: Grove Press, 2001.